.

The trouble with color matching

Christiane writes: “I have a client who’s choosing the colors for her business. I’m currently designing a business card for her based on the paint colors she will use for her studio. I got the paint swatch for a green, and I’m trying to find a similar CMYK color in my Pantone “Solid to Process Guide Coated” swatch book. It’s been difficult, and so I was wondering if that’s the way to go or if there’s another technique out there.”

————-

Hi Christiane,

As with most things graphical, there’s a short answer and a long answer. The short answer: Pantone’s Solid-to-Process guide (now called Color Bridge) will give you the closest CMYK to a given Pantone solid. But that represents a small fraction of the millions of possible CMYK mixes. Rogondino’s Process Color Manual will give you 24,000 printed CMYK swatches, which will get you in the ballpark, but it’s still relatively few.

But here’s the thing to know: You don’t need a perfect match. Even if you could roll her wall paint right onto her business card, they wouldn’t look the same.

There are several reasons why. One, we perceive big color (the wall) differently from small color (the card). Two, light falls unevenly. Look around your room and you’ll see direct light here, indirect there, and different intensities and colors (incandescent, fluorescent, daylight). Three, nearby colors affect perception; green next to blue looks yellower than green next to yellow. Also, colors get flavored by colored light reflected from floors, ceiling, and so on. The lighter the color, the more it will be flavored by other colors. And, of course, green on your printed material (reflected light) looks much different from green on your computer screen (projected light).

Your goal is to get the perceived color as close as you can. Green next to black, for example, must be darker than green next to white in order to look the same. Green in a dark hall should be lighter than green in a light room, in order to look the same. And so on.

But now I’m inching toward that long answer.

In your favor is that green is the most diverse color in nature. There are more variations of green, by far, than of any other color, so you have a big palette to work with.

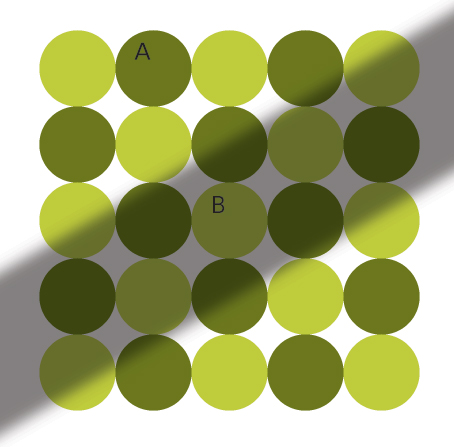

(Above) Which circle is darker, A or B? You fuss getting your two greens just so, then a shadow crosses the wall. What happens? Your mind compensates for the shifting light, so circle B still appears lighter than circle A. Your swatch book, however, will tell you that color B is both darker and grayer (inset).

The takeaway: Get your colors as close as you can, but don’t sweat perfect. Close enough really is good enough.

The takeaway: Get your colors as close as you can, but don’t sweat perfect. Close enough really is good enough.

Final note. If you’re working with a swatch — like a Pantone color — stick with it, because it gives you a standard starting point. Just don’t expect someone viewing it at the mall to see the same color as another viewing it online or outdoors or in a dim restaurant. They will all see something different.

.

.

Another useful point that I often use is to somewhat ignore the color (which includes the hue, the saturation and the relative lightness or darkness) and concentrate on the hue (which is independent of saturation and tone).

Matching the hue as closely as possible will get you into a useful ballpark for anything except the blues, which tend toward violet in almost any CMYK rendering. It’s mismatched hues that grate on the eyeball.

In your example, the light, dark and shaded spots are (almost) identical in hue.

Great post, thanks for the simple answers to the question (even the long answer).

I was wondering what you thought about tools like Pantone Colormunki and ColorCue?

Thanks

Simple solution — and I’ve done this for decades with no complaint from clients, because they match the color from my swatch books: Pantone and Trumatch steered by my suggestions. If they are not local clients and have no swatch books, I give them suggestions and tell them to go to their local printer, Kinko’s, or Staples, and look at a swatch book. I never choose a print color based on CMYK screens, because screen color is not print color, and also because various printing presses can output very different colors. I still do press checks and urge my clients to accompany me, so we get what we want. Also, after getting to know a printer, I know which ones can match color well.

Your answer here is brilliant, btw.

Part of the problem here is that the client is the one often asking for the perfect match . . . and they neither get nor care about reflected vs. projected light, and differences in perception. They want exact, because that’s what is in their heads to demand and expect from a modern designer.

Um . . .

In the sample above, the B circle does not look like the B swatch.

is it a tint perhaps in the B circle?

Alby, the B circle and the B swatch are identical, but your eyes will not believe that, which is the point here.

We have always worked only in on-screen, never print — usually big screen (presentation design) but also interactive (computer screen).

It has always been an exercise in patience to deal with clients and even traditionally minded designers who split hairs over colours we have put together that they are viewing on a computer screen.

Hmmmm, they say, I think it’s out a little. I say, “Well, I can make it “right” for this monitor . . . then what about your boss’s monitor? Or your client’s? Or the age of the bulb in the projector at the conference you are presenting at? Or whether the venue technical staff have the ambient lighting running at 30% or 40% brightness?

Every one of those parameters will change the colour by much more than tweaking it one or two Pantone colours up or down the chart.

Very good, succinct answer.

But like JoshuaCreative said, clients expect exact, even when it really doesn’t exist. (And let’s not even mention the fact that different people perceive certain colors differently.)

I think this is so because the graphic arts industry has bent over backwards to tout color fidelity in all media. While it is true that closer matches can be made with all sorts of expensive systems, it is never truly exact. It can’t be.

I really enjoyed your article. If they don’t believe their eyes they should test it for themselves. I did. Amazing!

I have the same issue with online design — everyone has their monitors set up differently, so there are no “exact” colors on screens, either.

Thanks John, a very helpful article that I will be sending on to any colour-challenged clients. Explaining colour differences through different media and placements is tedious to do, and so it’s important to show it’s impossible.

After having to reprint a legal firm’s business cards twice when they “didn’t exactly match their counter top,” I took the Pantone book, sat it on the counter and asked them to point and select their own colour. Actually bought the whole tin so we didn’t risk mixing wrong inks and . . . yes, still not happy! Bending over backwards to match it was pointless and expensive.

Yes, close enough IS good enough.

Good answer/explanation. The circles with shadow is a perfect example and a fun eye teaser! I took a little screen capture of circles A and B and put them next to each other — not because I doubted you but just ’cause it’s fun to really see how the eye is fooled!

@John and Alby — Agree with Alby. Looked at the colors thru a hole in a white paper, not influenced by context. A looked darker than B.

Haha,

I did a command+shift+4 screen shot 80x80px of the B circle and the B card because I couldn’t believe it!

Turns out they are the same.

This is a fascinating exercise. I wasn’t trusting my eyes, so I let Photoshop do the convincing.

Alby, if you open a snapshot of the graphic and sample the colors, you’ll see the difference. Indeed, B is darker.

Thanks for a great post, John.

With clients wanting to match print to paint, which is what you have here, there are a lot of variables. The working solution is to establish a visual close match in Pantone, coated for glossy finishes or uncoated for flat paints. Generally, that has been successful for my clients over the past 30 years of paint-to-print work. (Sign shops do this daily.)

If perfection is desired, and budget is no matter, I recommend a spectrophotometer (ColorMunki or i-one) to establish to L*A*B color of the wall. The SOURCE color is your wall. The device reads the color, then using an ICC profile of the medium you wish to print in (the DESTINATION), cross-references the color to a CMYK formula.

Spectrophotometers are handy for this — we use ours daily — and it gives us a reading of whether we can do the desired color. Acceptable is 2-3 Delta E (a measure of 1 Delta E is the difference the human eye can discern in color).

Important — you may not be able to reproduce the client color in CMYK or PMS; paints have different pigments than inks, and the UV effects of the pigments alter how we humans see the colors. The term is metamerism, and the viewing light color affects the client’s perception of the color. So even if you get a 1 Delta E match to the color, it may not compare in the same environment.

Furthermore, to be successful with dead-on matches, you need a destination ICC profile that is fresh and reflects the press or printer you will output to.

I recommend that your client select a color that is reproducible (for economy) in CMYK space, and then take that color to Home Depot and have paint matched by spectrophotometer to the print.

Well explained and thorough answers. I hope it will definitely guide the designers to have multiple perspectives for satisfying customer needs.

You can see two examples of this illusion here:

danariely.com/cube-visual-illusion/

and here: danariely.com/checker-board-visual-illusion/

If you’d like to learn more, search for the term “metamerism” on the Google intertubes. Be prepared to furrow your brow in concentration.

Really interesting question, and answer. As a designer, I think it becomes instinctive to make adjustments to colour based on the environment — without really stopping and thinking why. For instance, a corporate solid colour will always need to be lighter than the same version of a colour they use in text.

The “illusion,” to me, is that people tend to treat colour as a finite. “Is it yellow in here, or is it just me?” is, in my opinion, closer to reality.

Most people will have a perceived colour memory; that is, they really are convinced that they know what colour objects are meant to be. As a scanner operator, I had more trouble satisfying the client when the images contained everyday objects like tomatoes, apples or grapes. Even though I was matching to the originals, I could never match the client’s perception of the colour of these objects. Yet when scanning automobiles or manufactured goods, the client never questioned the colour match.

I had a real heart-stopper designing in CMYK, getting the client’s approval, and then scrambling to find a matching Pantone. I was lucky — that time. I like lindro’s getting the client to choose the color from his/her books. Anyone have a recommendation on how to best manage the client’s expectations before the process starts?

Using the Mac utility “Grab,” I did a small capture of the various colors. A and B circles match the respective swatches, dead on. Very weird. The Photoshop sampling technique is also a good check. Viewing through a hole in white paper doesn’t work, not sure why (color memory?).

Nice exercise. It helps explain why I had to go three shades lighter to get the yellow in the master bedroom to “match” the yellow in the front hall. Walk from one room to the next and you have absolutely NO sense that the color has changed.

This colour discussion is really intriguing. To the naked eye on the monitor, they are very different, so I also did a screen capture of both A and B circles and pasted them into a Word document, and when I look at them side by side in that document they look the same. However, when using a little utility called “Instant Eyedropper” to measure the colours on screen in both RGB and HEX, they are different. A = 109:119:30 or #1E776D and B = 103:110:43 or #2B6E67.

Wow! I, too, just could not believe that the B circle and the B swatch were the same . . . until I cropped them and set them side by side in Photoshop. This really proves that we cannot trust our eyes . . . I’m amazed and humbled.

What a great lesson!

Excellent conversation and instructional input, particularly from Brad, thank you.

Thank you for posting such a succinct and thoughtful explanation of this topic! I will definitely be sharing this post with my clients. I am thankful that I took a color class in college — it comes in handy on a daily basis!

Also, it will look like a different color depending on the type of paper it’s printed on. Shiny paper will appear brighter, while a texture paper may soak up the ink and appear darker.

Here’s a thought to try . . . get a small sample jar of the paint, and paint it on a board that is roughly 24×24 inches. Hang this on a wall, then pick six colors that “by eye” look similar to the wall color. Match the swatches to the color to see what is most similar, and ask your client to review them as well. Most importantly, “educate” your client on how color is not going to be exactly the same depending on lighting, etc., and that the goal is to pick a color that they perceive as being the same.

The other option that I would recommend is to pick a Pantone first, and then have the paint made to match . . . this is a much easier process.

I struggle with color and this article really helps explain why. The color example is amazing. Thanks again John for another great article!

I recently learned the hard way about reflected/printed colors. I created a CD sleeve with a rich blue background (on screen). Unfortunately, the printing company didn’t warn us that our CD covers would resemble Spinal Tap’s black album when printed. Needless to say, I immediately went out and bought a swatch book.

Good article, as always. I do have an issue with some of the comments, however. I really wish designers would learn proper color terminology: hue, value, tint, tone, shade, etc. The are used incorrectly in many of the comments and, irritatingly, on the home and fashion design shows that overrun TV.

How about an article reinforcing correct use of the color terminology?

O my word — that’s freaky — they’re exactly the same colour!

Hmmm, I’m wrong — used the eyedropper in CorelDraw and B IS actually darker!

Let me add some other CMYK variance into the mix:

All surfaces produce different colour results, all printers produce different results, even the same printer operator will print it differently on a different day! A logo may have a colour cast from the work its printed with, and what’s more, all people have a measure of colour blindness or difference in how they see colours, so if you have more than one contact in a business, they will see the colours differently from each other! Add to this, the previous swatch you’re matching to has faded slightly since the last time it was printed!

Even PMS ink won’t match on the “same” stock from a different supplier. ARGGH!

Close enough is good enough — in fact, it’s a miracle!

Even black isn’t always black. I use a mix whose total is less than 200%. Works great.

First of all, paint pigment, printer’s ink, and computer screen will give different results. I think your client is caught up in a “matching a painting to a couch” mentality that sooner or later will change, because the couch gets replaced or, in this case, the studio gets repainted.

As a designer, you should urge your client to pick colors that reflect her business and not her environment.

I always put together some PMS color combos and/or print samples to show clients options for their business look. Most often, it is up to us as designers to take the time to educate clients about the printing process.

I won’t decide on the color look. Instead, I will ask my customer for a piece of cloth, wallpaper or whatever was used while shopping for his/her preference and use the matching color as CMYK for the printer.

Excellent post; fabulous, instructive comments (esp. you, Brad). I concur with those who suggest that the client make the decision and also with those who understand that it is a process, firstly, of educating the client.

Perhaps your little experiment would be useful to clear the air with a client, as well as having a sample of the same swatch on different media, seen on screen, in different environments, etc. It is crucial to understand that it is perception we are dealing with, and hence, subjective and subject to the vagaries of the different systems. (Taste is analogous: a good part of it results from olfaction, and then, how many taste receptors do you have for which type of taste? How many rods and cones do you have? that sort of thing.)

Another good approach is to select, at the outset, a color that is actually printable . . . lots of toothsome stuff can be out of gamut. Subtractive/additive color models operate differently, and light dances more readily than pigment on paper.

Again, this is an art form. The client must be taught that we are not all robotic machines that perform similarly across all conditions: Expect pleasing reality, not theoretical perfection. Kudos, gang!

That was too freaky! I did a screenshot of the swatches because I did not believe it, and I’m still freaked out. Wow — go figure — thanks for the insights. Awesome as always.

Buy a Pantone Color Cue on Amazon (a little over $200), put it on your client’s wall, show them the Pantone color that it recommends, and voilà!

on Amazon (a little over $200), put it on your client’s wall, show them the Pantone color that it recommends, and voilà!

Good ‘n’ simple explanation! But technically, I’ll recommend that Christiane could try the RAL color palette, because it shows painting color codes for different objects. Maybe function for that case. Thanks!

I genuinely thought maybe the wrong circle “B” was marked until I took a screen capture and pasted it over in my image editor. I was stunned. “B” is darker! What a fabulous example, and it really opened my eyes. Thank you!

Great Article! I am printing it out and plastering it all over my office for my clients to read. And boy, do I have picky clients!

WOW! I had to copy your graphics into Photoshop and both sample the colors and cut and slowly drag a section of A down near B before I believed it. I wanted to see it for myself. That’s fascinating. I really dislike color matching . . . I’ve spent countless unbillable hours on it and don’t care to do that again. This was a little reassuring!

As an ex-printer, all this talk of colour matching brings back memories. The hours spent mixing inks, the days spent making sure print one off the press matched print 10,000. So glad I don’t do that anymore. Great article, as usual, John. Thanks. P.S.: Is there a way (I am not aware of) of capturing your videos, as I want to keep them with my PDF collection. Thanks. Ron.

Think outside the box: Pick, with your client, a Pantone color that they like, then take a swatch to the paint store and get computer-matched paint. (Everything said about perceptions and ambient light will still be true, but the client will feel that a match was achieved.)

Great article. Fascinating comments, all.

I read a really helpful explanation for me in the book Real World Color Management, by Bruce Fraser, Chris Murphy, and Fred Bunting, that I will try to share.

CMYK and RGB recipes are not colors in themselves but simply control signals for a color imaging system.

The color event doesn’t happen until the imaging system converts the control signals into imaged color, and the light from the imaged color reaches our retina, where it is converted into electrical pulses that travel along the optic nerve into the brain and are compared in our memory to any personal notion of what the subject should look like.

The challenge in matching colors are the great number of variables in the system. People are different: different eyes and different memories. We are looking at different images: designer’s monitor, client’s monitor, proof print, press run, cloudy day, sunny day, this paper, that ink.

Color management is the science that reconciles some of the variables; it doesn’t know anything about your memories, but it can alter digital color recipes so the appearance of the imaged color remains as constant as possible for most people. That is something.

Still . . . sometimes close has to be good enough.