Reader Mark Scholmann dropped us an email Tuesday with a question:

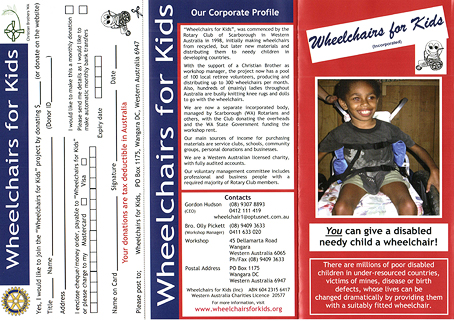

“I support a local charity group that manufactures wheelchairs for kids living in war-torn and less-fortunate locations. I’ve always been struck by their gaudy brochure enticing new donations to their cause and wondered if its ‘eye-catching’ design is really effective, or would it be better if it were more streamlined and less loud? That is, does this blast of the senses actually get more attention than a more ‘designed’ brochure?

“I wondered if you wanted to use this example as one of your discussion topics. Of course, any redesign and suggestions could ultimately help a very worthwhile group in their endeavour to help others.

“Wheelchairs for Kids is located here on planet Earth.”

—————

Mark, great question, great issue.

How designed is too designed? Wheelchairs for Kids is a bootstrap operation with a beautiful mission, sustained by unpaid volunteers. It’s clear that no professional attention has been paid to brochure design. Would a more polished look add to or detract from the soul of its message?

(By more polished, I don’t mean slick. I mean more intentionally presented, with visible thought given to a theme, a style, typography, photography and all the rest.)

This is not easy to discern. On one hand, there’s a matter of credibility. Does the kitchen-table design give you confidence that a real, well-run charity is handling your contribution truthfully and well? On the other hand, might a more-professionally designed piece broadcast a sense of wastefulness? After all, we want our money spent sending wheelchairs to children, not designers to dinner.

I’m not an authority here. My closest charity-design experience is the logo I made three years ago for Twinomujuni orphanage in Kabale, Uganda:

Twinomujuni (pronounced: twin-ohm-zhu-nee) is a similarly bootstrap operation that cares for orphaned children, of which in Africa there is no shortage. My goal was to give them an unpolished look that captured, in the colors and earthy style of Africa, the exuberance and hopeful resilience of youth.

Although I’d loved to have developed the whole project — Web site, newsletter, all that — I knew I didn’t have the time and that everything else would remain undesigned, so the logo would have to do the heavy lifting. My goal was to make it strong and vivid enough to bear that weight.

So readers, what is the role of design in these cases?

Let me suggest this: that the most authentic route is to forget “message” and “target audience” and other marketing-speak. Charity is not about putting on a show (“cheap paper, can’t look fancy”) or twisting arms. Rather, your work should portray, visually and verbally, in the purest, most elemental way, who you are. This is a job for the team, not just the designer. If you can actually make that visible, results should follow.

Talk to me.

This post really hits home. I run the in-house media production department for an international non-profit. All the issues raised in this post are ones that our department struggles with every day. And please forgive me if I’m preaching to the choir from my soapbox.

The idea that because you’re a non-profit your promotional materials (i.e. brochures, website, videos) must look like they were executed by an untrained staffer in order to be considered legitimate, is a fallacy and one that needs to be quashed. Potential and current donors are not impressed by promotional materials that look homemade. I’m not, and neither is anyone I’ve spoken with on the subject.

The misguided belief that “fancy” equals expensive equals wasted money is also a fallacy, and not one to which I subscribe. A poorly executed promo piece (even a well-executed promo piece) on cheap paper sends only one message. You are cheap. And not very astute in the ways of money management.

A well-executed promo piece on an inexpensive yet quality paper (they do exist) sends the clear message that you spend money wisely. And that’s the most important first impression you want to leave with prospective donors. Bootstrap or no, always strive to have your promotional materials project an aura of confidence and competence. Poorly executed, amateurish design does neither.

Then there’s the issue of “too much information.” The “Wheelchairs for Kids” brochure being a classic example. The too-much-information scenario is based on the mistaken assumption that in order to be effective your brochure or website must include every possible piece of information it is believed the prospective donor/supporter might need no matter how inconsequential.

Supporters want to know who you are, what you do, where and how effectively you’ll be spending their money and how to contact you. That’s it. Any more information than that will become an eyesore and only serve to confuse “who you are.”

I agree with Mr. McWade’s assertions in the final paragraph of the above article. Follow those guidelines and you will produce work that will effectively communicate both visually and verbally the essential message of the organization for whom you’re creating promotional materials.

P.S. Diggin’ the Twinomujuni logo.

I am not doing any right now, but I spent ten years building a graphic design business, and I can tell fledgling designers that pro-bono work for non-profits is maybe the best way to get established and build a portfolio. The smaller the charity, the better. And don’t take paying work away from designers who currently do it. Just walk into any Chamber of Commerce or tourism center and see what non-profits have the worst-looking material. Take it home, produce a remake, and offer it to them gratis. I cannot tell you how many paying jobs have resulted from me doing this. Not from the non-profit. In many cases, I continued to do their work gratis, but the new paying work came from their donors who were impressed, asked about who had done it, and were sent my way by the staff and administration of the charity.

But I do understand the dilemma of looking like you have too much money for a non-profit. My first suggestion is that if you do it pro bono, make sure you put something like, “Design services for this brochure donated by xxxxxxxxx.” Good publicity for you and solves the “Why are they spending money on this?” problem.

And I truly believe that the design solution is something that BA mag has been preaching to me since I received Volume 1, #1 — simplicity. Good design doesn’t look expensive to the non-designer; it doesn’t look like anything. They don’t see it. It is invisible. Good designers see it for what it is — beautiful, simple design — but the general public sees it as a brochure/website/flyer for a good charity. As an example, a website I produced for a charity would not have a single animation, no movies, nothing that was flashy (pun intended), just the message. So much more effective. My goal in designing for non-profits . . . KISS. And we all know what that means.

John, thank you for making me a better designer. Every time I produce a new piece, I realize how much your words of wisdom over the years have influenced me.

Yeah! What Jim said. Do that too. So many small non-profits suffer from the lack of resources to acquire first-rate design. Offering your services pro-bono will allow them to redirect their resources to better support their main purpose. And any smart non-profit administrator will love you for it.

Well said Jim. I agree. “Good design doesn’t look expensive to the non-designer; it doesn’t look like anything. They don’t see it. It is invisible.”

Great post Jim!

Ken, your last sentence says it all — “Good design . . . is invisible.” As a graphic design educator, I always try to impress upon my students that good design is invisible, allowing the content to shine through. That said, the content needs to be organized so that the intent is clear and straightforward.

Great topic!

Appreciate and agree with Jim’s post here, especially the bit about simplicity. Great design can be compelling, beautiful, and marketing-smart without being too polished and snooty!

Jim gets my vote for best post. He hit it when he said the public pays no attention to the design, only the message within. Or to further mangle Jim’s words, they don’t know why they’re impressed. They just are, and that’s the magic of good design.

Great points about good design not needing to be (or look) expensive, and for designers to offer their services for free to build a portfolio or help out a worthy cause.

IMHO, there is no excuse for bad design, even when done by volunteers using basic software. Choosing harmonious colours and laying something out nicely don’t cost anything!

This post reminds me of a great previous Design Talk post, “Ode to the amateur logo,” where it was suggested that top-notch design could be inappropriate for a small charity.

Nick

Agreed. The nonprofit for which I work does exactly this. “Funding for this project comes from xxxxx.”

I’m a marketing director for a good-size company (Palram Americas) who also does some freelance work on the side (¢ensible Marketing). Because I have a full-time job, I don’t like to spend a lot of time or money finding side-work, and I prefer to take “jobs” that I can convert into long-term, sustainable clients.

I recently volunteered to build a web site for a very local cycling group who wanted to raise funds for one of their members who had gotten hit by a car (ride4matt.org). Over the course of four weeks prior to the event, I built the web site and updated it as required. I listed myself as a sponsor in the sponsor’s area, but will now use John’s suggested phrase going forward. Fortunately, the emcee gave me plenty of kudos at the event and let people know I had donated my time.

The result? A prospective client, who I had never met, approached me casually at the event to express his thanks for my involvement and find out more about what I do. I explained that my forte is to make small marketing budgets look much bigger than they are through smart, cost-effective design. He followed up with me the next week to set an appointment to get together. Based on his first job, it appears that it will be a decent paying, long-term relationship.

Oh, and the best part, the event generated approximately $10k within about four weeks by attracting a host of small and large local sponsors and about 400 participants to the event.

Well worth the effort on all accounts.

John —

It’s more than a little ironic that you placed the critically important concept: “By more polished, I don’t mean slick. I mean more intentionally presented, with visible thought given to a theme, a style, typography, photography and all the rest.” within parentheses.

Rarely, if ever, have I heard “polished” so well described — especially within the context of graphic design.

Clearly and effectively communicating with clients is the cornerstone of a successful creative engagement. Your clarification of just a single word — “polished” — brings a great deal of value to that effort.

Great words.

Thank you.

I could not agree more with what John says — it’s great summary for “design polish.” I have done some pro bono work in a similar situation before and have done exactly what Jim writes about: Put your credit text on there, and both sides win. The charity needs no explanation or justifications, and the designer builds her/his portfolio. People do read these credits more often than we think. My recommendation: Add your URL or some direct-contact information (email/phone number) for a higher ROI. People who donate are more likely to be in a stable financial position, which is good to know and deal with as a service provider of whatever kind, isn’t it?

To me, a bad designed whatever always means that the people in charge don’t know their outcome clearly, because if the outcome is to communicate their message, a good design will do it better than a bad one. Trying to save on the design is like not buying a saw when wanting to cut a tree. I associate not knowing their outcome with getting a bad result and therefore avoid dealing or supporting those whatevers.

Having also done many pro-bono design projects (coincidentally for Rotary here in Australia), I agree that one struggles with the idea of “looking too flash.” To me, an attractive, clean design always appeals more than piles of info. Looking at the “Wheelchairs for Kids” website, this would seem to point in the direction that the leaflet could take. It’s a simple look but pleasing to the eye, and the headline title immediately gives you their message in a nutshell: “You can give a disabled child a wheelchair.”

As always, Before & After has offered an inspiring conversation!

How timely!

I have just received our local Town Hall Civic Newsletter, and it displays many of the “qualities” of the well-meaning amateur let loose on a folder full of fonts, colours, and rules. I was so upset by the design that I looked for and found on the back the name of the printer. I called them and we had a conversation that went something like this:

“Hi, Mike, how can I help? You’re calling about the newsletter — what is it you want to say?”

This was warily put, so I went gently. “How do I put this without offending? — It’s awful!” To which he replied, “Oh, thank goodness, I thought for one minute you were going to say you liked it. We just print it, and it makes us cringe every time it goes out. We hate having our name on it, as it doesn’t make us look good, either. It’s produced by someone in the town for free, and we have tried all we can to assist in helping the design — we have to do so much to put it right before it can be printed as it is, but how can you beat free?”

How do you try to raise the level of communication between a town and the people living in it when the message is being delivered in a vehicle that, seemingly, has had very little care put into it? I don’t mean by the person who did it — they probably spent hours and hours on it — but the Town Council thinking that that is the best way to convey a message. Or do they just say quietly, “What do you expect for free?”

But there is another side of that coin, and this is a question I want to ask: Does everyone automatically see bad design for what it is? Is it self evident? Do those who don’t see bad design as being separate from good design even care? Are those people design illiterate? Does it take a design education to see the difference? Is it learnt or inherent?

As someone put it more aptly than I ever could — “You don’t see good design, it’s just there, quietly doing its magic.”

If anything, I would suggest a shoulder-to-shoulder shoot-out with the Wheelchairs for Kids leaflet against the “designed” version to see which is more effective.

Author Robin Williams calls them VIPs. A visually illiterate person cannot decode design. They may like a design, but they can’t tell you why. One step up from VIP is the person whose vocabulary is limited to words like “clean” or “pops.” Then there are the designers themselves, who by no means have the keys to the kingdom. Many designers can’t explain their work, either.

Totally agree.

All of my design work is for local charities that I otherwise volunteer for, along with my church.

At church, if I don’t get asked to do a project, I hear from the parishioners very soon after about it. Someone thinks they’re trying to help me by not asking for yet another project, so a print ad goes out in Word. As soon as it’s published — always without my knowledge — I hear about it from half a dozen parishioners about how bad we looked, and I’m slipping!

Two of my charities have been blessed with an amazing local designer’s work for some time. It makes us look professional, well managed. In one case, that designer no longer is able to donate his services, and I’m starting to work with them to take on the legacy. It is such a pleasure working with them, and they are so grateful. Since the old designer left, the new work was all done in Publisher by volunteers, and it looked terrible. No way I’d want to donate money or time with that stuff being put out. It says “we’re going to hell in a hand basket” in 72-pt. bold lettering!

I started working with another charity I’ve been associated with for years on a redesign on all their brochures. The executive director is a micro-manager, and after blowing six months of really painful back-and-forth on a single brochure, which they loved, that director asked, “and I need it redone in Publisher so our volunteers can change it. And, eliminate all hyphens. Then add two spaces after every period — it makes it much more readable.” I canceled any further work with them and told this director, who is a friend of mine, in no uncertain terms that’s why this stuff looked so horrible and unprofessional. What can you do? People know my work well locally, and I can’t let my own reputation be that damaged, no matter how much I wanted to help him.

My experience for the past several years has been very positive with a couple of minor exceptions. Pick and choose your charities with care. Stop wasting your time if that first project is a nightmare to work with them. There are too many good charities out there that would love to have your help. For the most part, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed my work. It’s been so rewarding.

Good and bad design both get noticed. Good design gets donation checks and volunteers. Bad design drives them away.

It’s not the design that “drives them away.” It’s the attitude of the charity. One of the LGBT groups in town I work with always says, “thank you for your generous donation.” It could be $1. It doesn’t matter. You are always genuinely thanked — and not harassed every week for more! I’ve received a single, handwritten note from them or a nice thank-you call for very small donations. I just want to give them all kinds of volunteer time and money because of how I’m treated. I gave one national charity money every time I walked by their seasonal campaign buckets. Then I made the mistake of giving them a check, which generated weekly appeals for money. I’m pretty sure they wasted every dime I gave them on donation appeals to me, and a good deal more. I’ve never given them a dime since.

When I looked at the brochure, I tried to shift out of Designer Mode and pretend that I received this in the mail. All the elements to draw a donor in are there — photos that draw you in, a strong name for the organization, asking the reader directly to donate. HOWEVER . . . the brochure is incredibly hard to read. I wanted to read it but couldn’t even skim it! And that made me wonder: How many potential donors did the exact same thing?!

I agree with previous posts: There is a huge difference between thoughtful, intentional design and FLASH! This is definitely not the type of project you’d want to put embossing or gold foil stamping on. But it could sure benefit from “intentional” text layout, a hierarchy structure of headlines, thinning of the copy text, etc. Clarity of presentation would only benefit a worthwhile charity.

@ Jim: Great suggestion to benefit local non-profits and build one’s design portfolio! I’m definitely going to give this a go.

@ Ken: Great post, well written.

@ McWade: Thanks for another great discussion topic!

Good design doesn’t necessarily mean just pretty to look at. Good design presents essential information in a well-orchestrated hierarchy of information to achieve the goal: communicating your message efficiently and effectively to the target audience. While there are some untrained staffers who may have a creative knack, if you want to achieve real results, hire someone skilled to get you there. Professional design should be viewed as an investment, not an expense. When building a house, a solid foundation may be an expense, but it is also an investment to protect everything you plan to build atop it.

I just ran into this same dilemma with a potential client. They are not a non-profit but a small company selling to a rural market. The representative felt if their materials looked too professional then prospects would feel the company was too big and not the friendly, small-town business they are.

I wish I would have had these words to combat his theory.

Thank you for this thought-provoking post!

I agree with all the points made. But other issues are in play, too. I work for a non-profit, higher-education institution. Many of our internal departments balk at the idea of paying for our professional design or photography. They think they should get it for free, and would rather have their secretary “design” a brochure and take photos with a cell phone. Many don’t value professional input. And they don’t understand the value of white space. I often get the comment — “Hey, fill the space!” I was also told that color printing “looked too expensive.” Good design is an uphill battle, especially when so many amateurs are doing it for free.

As a designer for a non-profit, I can attest that sometimes your own staff is, unfortunately, your enemy. The white-space battle gets fought a lot, as there is always a ton of text that they want to put into the shortest, cheapest document possible. Also, the notion that a knack can substitute for a design degree. Frustrating!

Thanks for a terrific article.

Hear, hear, I agree with you all.

Give back to your community by giving your time to a charity that thinks they can’t possibly afford a “professional.”

Put your very best into it, and it pays back — you feel good about helping out, and you never know what may come in the future.

For those starting out, it looks great on a résumé.

I love this! I did a brochure last year taken right from the archives of Before & After . . . the wrap-around brochure. It was for a non-profit recreation organization that raised money for kids.

I took out all of the repetitive information and put on faces of kids, a call to action just like your article indicated, and that wrap-around corner was so unique!

Ken’s questions above are essential to answer . . . If I give money, where is it going? Who does it benefit? How is my gift going to change lives?

Maria

A business, whether non-profit or for-profit, should portray the same message: We are competent, professional and worthy of your funds.

When a design company wishes to donate a portion of its design work to a non-profit (it should be a percentage of overall business, say 10 to 15 percent, in my opinion), it not only gives the non-profit credibility, provided the design work is well done, but it gives the design company an opportunity to give back. A bonus is that the design company receives a community-driven image, which is always a good thing.

With both my freelance business and the company I currently contract with, we do just that. We do it because we care about community. However, we try to be careful about how much we give away. We have to remember that we’re all in business and we have to be responsible in that regard.

In the same way, any non-profit is in business to do a certain thing, to provide a particular service, and do it well. That’s the point.

Well-thought-out design gives any business credibility. In the case of “Wheelchairs for Kids,” good design will ultimately increase their reach and will most likely increase their incoming donations. I don’t believe there is any difference between a non-profit and a for-profit in regard to the need for a professional image. Design is a huge part of this.

A phrase that comes to mind (I may even have gotten it from you, John!) is that all things are designed, but not all things are designed well, and good design does not necessarily have to cost more than bad design. Jim’s suggestion about donating design services and noting that on the piece is a great one if the perception would be that cash donations would be “wasted” on something as frivolous as design. (Not saying at all that design is frivolous, just that there are a lot of people out there who feel that it is.)

The point of a brochure that is soliciting donations is to make the process as easy as possible by making it clear what the purpose of the charity is, how the donations are used, and how to make the donation. A well-designed brochure that successfully does this is going to bring in more for the charity than a poorly designed one that gets tossed in the trash. That in itself is also performing a service for the charity, is it not?

One of the main segments of my business in design and marketing is working for non-profits, and doing what I consider to be extremely important work: communicating their message and mission professionally to the audience that wants to hear what they have to say. I’ve been doing this for almost 15 years, and I have had many nonprofits of all sizes as clients throughout that time.

I am in full agreement with Ken Wilson’s post. Inconsistent messaging or brand, and poor execution, is no way to garner attention for a worthy non-profit. The way to get the right attention is to communicate in the most professional way possible. This doesn’t have to mean glossy trade magazine ads or hiring a top ad agency to develop an edgy ad campaign.

It means, work with a design/marketing professional who will help you get to the core of your efforts and pull out and craft the messaging that will work for you. Listen to their advice when they pare down your copy to its most important bits. Be judicious but deliberate in your choices of imagery. Find the emotional pull that will make an impression on your audience.

Then stay consistent throughout all of your marketing efforts, so you have a strong, well branded, cohesive look and voice to everything your donor and supporters touch and feel. The design work should be done by a designer, not someone who happens to own a page layout program. Donors pay attention, and they respond better (be it volunteering, joining, or writing a check) when they feel confident that the org they are getting involved in is professional. Inconsistent branding, or confusing, badly organized materials are a surefire way to look just the opposite.

In addition to our paying clients, my own studio has a giving-back program where we work with an org or two a year at a reduced rate or pro bono to elevate their message and brand so that they are on a level playing field with other orgs like them. We believe it’s the right thing to do. Our most recent pro bono launch is http://www.freedomswings.org.

I agree completely with your assessment, John. The bulk of my clients are not-for-profits with little money to spend on their marketing. Often all they have is a logo, so we start with that. I talk to them and show them how they can build on that, first by setting up guidelines for how and where to place it, and how to respect it so it can do the heavy lifting. Next, how we can use the colors and the “feel” of the logo to establish the larger identity standard. Sometimes these groups have managed to get a decent logo, but often not. In the actual designs, I start by reducing the clutter, tidying things up using the same principles you illustrate in Before & After.

Inevitably, someone in the organization will design something in-house: “It was just a little flier we passed out [to hundreds of people].” Or a new staffer will farm out a project to someone they worked with in the past — “my brother’s friend who works really cheap.” My goal is to make sure the org can sustain a consistent, meaninful look regardless of who is doing the work.

I agree with what’s been said so far. On one hand, having undesigned promo pieces says that you don’t spend money on such things, but it also says that you’re not willing to pay attention to detail. (Do you also skimp on bookkeeping?) On the other hand, I have received solicitations from nonprofits that seem like they’ve spent too much on their printing and distribution: complicated die cuts, custom-assembled pieces, extra-postage shapes and sizes — and that makes me wonder about the organization, too. So I think it’s less about the design itself. (It would help, however, if they were to print “design and printing generously donated by _________” on the promo piece itself.)

Much of my current client base is nonprofit, and some clients understand the value of good design, while others don’t. Sometimes, at their request, I have to clutter up or “dumb down” a design. (This is another topic altogether.) This means I have a lot of work that I have to leave out of my portfolio, unfortunately. One current client, however, realizes that they’re not going to be taken seriously by their wealthier donors if their stuff looks unprofessional. They’re refreshing to work with, even though it’s unpaid work.

Interesting topic!

It can be perilous to ignore “target market” aesthetics completely. I think the previous comments are great and to the point and suggest that the “invisibility” of good design that Jim described so well can be used to selectively improve work like the WFK brochure. Patriotic colors and blocky, no-nonsense layout may indeed appeal to a certain cross-section of readers, while integrated colors, swashy fonts, or graceful curves might alienate the same group. However, the designer’s scalpel can still be applied to improve readability and to diminish the impacts of vibrating white spaces and heavy gridding. How about eliminating all the borders and frames, while retaining the vertical red bars on the backside, for a start? And filling in the white background of the logo to avoid the jangly, misaligned corners? Much can be done to remove barriers to communication without taking a stance on the overall aesthetic, which could imply a change of “brand” and impact the existing donor base.

Thanks for yet another interesting topic and informed discussion!

I would like to compare the cover of the brochure with the Yellow Pages ads you remade in your book. One thing is if the flier is to be handed out; another thing is if it is competing for attention with a bunch other other fliers.

Also, the inside could be better prepared for skimming the text — as I am sure most people do — to see if it is something of interest.

Conclusion: I am sure they could benefit from a professional hand or advice in order to spread their message further.

Just my 5¢.

Pia

I can’t agree more with what Ken and Jim posted earlier.

I’ve been a non-profit, in-house designer/design manager for 11 years. A piece that looks cheaply printed or cheaply designed communicates not thriftiness but that the organization may not be worth the public’s time, talent or donations.

Just like we judge people on appearance, potential donors, political contacts, clientele, volunteers, board members, etc. judge non-profits on their appearance. People want to hitch their wagon to a winning horse, pure and simple.

Non-profits are no different than for-profits — every contact with every audience is an opportunity to win them, retain them, or lose them. Why not err on the side of trying to impress them? It’s worked for my organization.

I agree completely that the presentation of information from a small operation — profit or non — should look professional, whether the work of the designer is paid or not.

I do have one suggestion about the particular brochure in question. Be very sensitive to color. And I mean extremely sensitive to color. The first thing that struck me is that the colors are the flags of colonizing countries such as the U.S., U.K., and, in this case, Australia. One of the big problems for medical services in underdeveloped countries is that their economies have been forcefully underdeveloped (a verb as well as a noun) by the metropolitan countries.

Do not make it appear as though you are collecting money in a richer country for children in a poorer country because you are a patriot. Collect the money because it is the right thing to do.

In this case, I would use colors that appeal to children. Not that children are going to see the brochure, but because it is evocative of the purpose for the money.

Extremely valid point about the associations with the colors. As a reader from outside of the U.S. living in a country where negative associations with the “colonizing countries” is clearly a reality, I couldn’t agree more. Think several times before using red, white, and blue!

People are inspired to donate to causes that are successful. They want to join causes that are “winning.” The design should show that the organization has its act together. Clean design helps communicate that the organization is effective at what it does.

Of the many things a non-profit needs to establish to successfully gather donations, the first is credibility.

Read the brochure. Does this organization look like it will be around for another year? How many children have they helped? Who are those children? Name one, and tell me his or her story. How much money have you collected? What is your goal for the year or quarter? How many other people like me have given?

Suggest levels of giving. Can I be a charter member for $500? Will you send me something so I know that I am part of a group that is making a difference?

Making a brochure on the cheap is penny wise and pound foolish. Low-income houses may be assembled by volunteers but they are designed by professionals. Do not hand this over to some kid trying to fill his portfolio. Hire the work done by an agency that specializes in non-profits, and see how soon it pays for itself.

Your goal is not to see how many people you can get to donate their work; it is to help as many children as possible.

These are good suggestions for improving the brochure. Most of the discussion so far has been about design; i.e., of making the brochure look professional but not too expensive, but it seems in this case that the problem is more structural. There just isn’t enough useful information in the original brochure to be very convincing. Would you as a designer go back to the client and say, write this again?

This is (in principle) like any other project. You want to engender a response in a target audience. To do that you have to clearly communicate your message in a way that appeals to them. If you do the job right all that readers will notice is themselves considering what choice to make.

I’ve done a lot of non-profit work for over 30 years. Some organizations can afford to pay; others I’ve done pro-bono.

What I’ve found is that non-profits are no different from any other organization. That means common design sense applies:

1. Design is credibility

2. Organized information communicates better than disorganized

The idea that an amateur throw-together (can’t bring myself to call it a “design”) gives the impression that donors’ money isn’t being wasted has not shown itself true in any case I’ve ever seen. Professional visual communication has improved the message getting through in any case I’ve been involved in, resulting, in many cases, in increased donations.

I have even been asked to place a disclaimer at the bottom, something like: “The graphic design on this project was donated . . .” They want to convey something like “Hey, this is professionally designed, but we promise we didn’t use any of your donation for that.” To me, that’s like saying, “Don’t think about an elephant.”

The reason this doesn’t work is that most people don’t think about design, or whether a piece was professionally designed or not. They just read a piece if it holds their interest, and organized information always holds interest better than a visual mess that takes work to get through.

On the other hand, this is decidedly not the place for embossing, spot varnish, 6-color waterless printing, or any other luxury (or on the web, Flash animation, never-before-seen jQuery functions, or other slick features).

In short, austerity is advised, but, like any other job, so is sound visual communication.

I work for a non-profit and do pro bono work for non-profits on the side. The thing that strikes me when I see “kitchen table” design is that it makes the organization look very fly-by-night. Nicely designed promotional material says, “we take ourselves seriously.” I just look at it as my opportunity to help a worthy organization and make the world look a little bit better in the process.

Having worked with many non-profits since 1984, I do know that there needs to be sensitivity between looking professional and looking like you’re wasting donor funds on “image.”

It’s not always a clear line, but over the past few years, people are much more accustomed to quality design from non-profits. This has been driven in part by lower-cost printing capabilities like digital print, more sophisticated web designs using low-cost templates, and so on. As a result, there is less likely to be a negative response to good design than in years past. But you still need to be cautious and sensitive.

In my experience, I’ve found that you can do small things that help remove the impression that you spent money unnecessarily. For example, the use of black & white images mixed with color often changes the perception. Even though technically it costs the same to print, people will assume that you spent less money when they see some grayscale images in your print piece. Also, size can make a difference. In the corporate world, bigger is often better, creating a “bigger than life” presence that stands out from the competition. But if you make your non-profit brochure large format, it looks like you spent more money. The same piece sized a little smaller than normal, even with more pages, will appear to be done with a smaller budget. Other aspects of your presentation are also important: Use white space instead of flood ink coverage if you can, use matte instead of glossy paper, forget blind embossing or die cutting if you want to avoid negative responses, avoid varnishes or aqueous coating, and, when practical, use slightly lighter weight paper stock than you might normally. All these things as a whole contribute to a sense that you were serious about minimizing cost.

In the end, design is about all those things put together, not just the visual styling itself. It’s the entire effect of communicating the brand and the appeal, including all aspects of what you are presenting.

Three main thoughts came to me when reading the posts and viewing the brochure: 1)The information must be easily found and concise in nature (how to give and why). 2) The design must appeal to the eye it’s attempting to catch, be it Joe Average or the average philanthropist. This means it has to compete in the marketplace of what crosses the kitchen table or the CEO’s desk, and good, clean design will make that job easier. 3) Badly designed anything turns most people away, be they design savvy or not — the design savvy know why, and the not-so-cluey are just as turned away, although more on an unconscious level.

I am not a designer, though I love it and do things for self and mates. So I’m speaking from that “amateur” level (although I was a Litho printer once, a long time ago).

John, once again a great process to get the grey matter working and folks talking.

Bad design is bad design (and this is bad design!). The comments here are mostly spot on, but my ten cents’ worth . . .

The leaflet needs to say who we are, why we are, and make a call to action.

It doesn’t have to look like a major corporation, but don’t dumb-down either. White space, minimal text, legibility, no clashing colours or fonts, restraint in everything.

Polished design = “to intentionally present one’s design with visible thought given to theme, style, typography, etc.” Agreed! Thanks, @bamagazine.

I favorited and posted the above statement on Twitter. Why? Because John hit the nail right on the head with this one!

Case in point: I recently worked with a new client who said, “Wow, the designs you did for me are awesome — so polished — thank you!”

You see — the thought I gave to the theme, style, typography, photography, etc., (regardless of a low budget) did not go unnoticed by my client — I’ve since worked for her on several new projects :-)

John: I’m in the process of redesigning my website and will be sure to have your statement: “By more polished, I don’t mean slick. I mean more intentionally presented, with visible thought given to a theme, a style, typography, photography . . .” on my front page!

Thanks for putting perfectly into words what I often try to explain to some design friends of mine. Thanks again John! You rock!

The sad thing about this is that the person who designed (or non-designed) this probably spent more time than a trained designer would to quickly put together a clean, informative design. Working in Word, or whatever other program, and not having the tools or design sense to lay out images and type often takes more time than a skilled designer doing a simple, clean design.

What’s the most important thing here? Getting the message out about the good work these people do. What’s the best way to communicate? Good design.

I’ve been reading these posts and agree wholeheartedly, with one exception.

I work with several non-profits directly as well as in a prepress environment. One thing that no one has mentioned is production costs. It burns me to see a designer produce a beautiful, slick, professional piece that the agency can’t afford to print!

Case in point: A local design agency produced a very nice annual report for a non-profit . . . 8.5 inches by 22 inches with full bleed! When we got it in prepress, we didn’t have a press that could print it, and none of our print vendors did, either. They were forced to either have the piece redesigned or find a large printing company with a press large enough.

I have seen this time and time again. The piece is beautiful but too costly to print. Many times I can “fix” it so that the costs are reduced without sacrificing the design — take off the bleeds, reduce the paper size, etc. — but not always.

To me, this is a waste of the non-profit’s resources. Why can’t the designers keep production costs in mind when they are designing? A few minor changes in their design would mean major savings for the organization.

As far as I see it, the disregard for a client’s budget constraints is just as much bad design as the look of the piece. Every single part of the mailer, leaflet, website should be relevant, and that includes making it economical to produce under the circumstance presented.

I have had jobs where a major car launch called for a specially mixed ink for the cover of the brochure to match the new metallic colour of the car exactly. That is their choice, just as it is the not-for-profit organisation’s choice to be cost effective.

Good design doesn’t cost, it pays. But it has to be good design.

Barb, situations like these stem from a lack of communication between the client, the printer, and the designer. All three need to convey their capabilities and limitations at the outset to avoid pre-press re-designs and other problems.

Although the client should take the lead in this, they may not know its importance or even what or how to convey it. When working with clients (for pay or pro bono), I insisted on connecting with the printer, and doing so avoided many headaches later.

All great points, and I’d add that choosing the right behind-the-scenes, who-are-we photos can validate the small scale, local vibe. Also, seriously, who doesn’t have a website these days? Isn’t that where they should put all the detail that doesn’t fit on the brochure?

John, great choice of topic. You make a powerful choice and statement by avoiding trying to answer completely and by making the point that design can’t fix everything. Anyone who’s tried to balance these kinds of considerations for clients — and it happens a lot now, not just with charities — can identify with the topic.

My background is in writing and editing. I’ve seen fine design get undermined by inadequate attention to text and especially to a balancing of the tone/voice of text and the style of the design. As for this particular question, I think it’s possible to “advertise” that the writing and design were donated and include the names of the contributors. Another option may be to use a service such as KickStarter to gather the money to put together a design package for a shoestring nonprofit. Also opens up a new awareness market for the nonprofit.

As a prospective donor, my first thought seeing this brochure (I get many like it) is that they do not care about excellence. In my experience, that attitude too often spills into other parts of what an organization is doing. The word “beware” comes to my hard-to-sell-to mind.

From an artist’s mind, my next thought is that this belongs in the round file. It has no appeal to me at all, except for the faces of the children and their need. Why not simplify it to that? A trip to their URL would answer any questions I might have.

The line between credibility and waste can be a fine one. I’ve worked in health education and non-profits for years, and more often than not, their collateral is horrible. What has worked for me is to keep it simple, clean and consistent from piece to piece. Use two color for print, full color and stock photos for web. Don’t skip on good design basics. Skip the Flash, sliders, fancy die cuts, glossy paper, and pocket folders. People like to give to charities that put most of their donations towards fulfilling the purpose of the charity. However you can communicate that in your design will be a big plus.

Having for many years worked in marketing for a not-for-profit, I have learned that a good design is the design that gets the most people to hear/read your message. It has nothing to do with the amount of money spent on a piece; there are many examples out there of pricey, poorly executed work.

With a quick glance, people should be able to know your organization’s mission, who you help, how you help them, what you need funding for, how their donation will be used, and how to give. Success stories, quotes from happy clients, and photos of local people all help strengthen the story.

(If the piece is for an event, make sure they know what the event is, who is invited, when and where the event will be held, how to register, and what to bring/wear. These basic topics are often forgotten and leave the reader feeling frustrated and your organization looking incompetent!)

IMO, the sample piece could benefit from losing the red borders and blue backgrounds. Instead, the color can be added to the headings and selected text to draw the reader to. When there is a lot of text, don’t underestimate the importance of white space, which helps rest the eyes and makes everything more pleasant to read. The audience might not understand principles of good design, but I think they know it (at least subconsciously) when they see it.

I think that we do pay attention to the design in that if it is illegible, we don’t read it. The Wheelchairs for Kids design looks like a Dr. Bronner’s liquid soap label, only not quite in such microprint. It’s confusing to my eyes, it would be hard to decipher, and I would give up.

So I say clean design. Doesn’t have to be Art, but geez, it can be eye-catching with a lot of white space, too, and basic design principles. And grammar, spelling and punctuation. (Not that this one didn’t, but I can’t read it, so I don’t know. And having seen a lot of this sort of thing, I suspect it may have problems.)

I plead for clear, simple and eye-catching.

Thanks.

I just learned of a maxim I’ve unsuccessfully conveyed to clients — and now I have the right words:

“The more you write, the less they read.”

Ten years ago, I moved to a new church and immediately volunteered to design their stewardship campaign materials. Previous materials were cut and pasted, thrown on the copier, and sent in plain white envelopes.

I did what I thought was a very tasteful, informative, interesting and thrifty two-color campaign unlike anything that church had ever seen. Maybe I was feeling a little too proud as I sat in my pew on launch day, until I overheard the two ladies sitting behind me say, “I can’t believe he’s spending all this money on ‘handouts’ — I’ll be darned if I’m going to let my pledge money pay for more paraphernalia in my bulletin!”

The next year, I used all color, lots of photos (including photos of the aforementioned ladies ;-), and made the design more approachable. I had never considered that perception before in designing for non-profits.

It seems that the general consensus here is that design does matter, and I couldn’t agree more. I wonder if anyone has taken up Mark Scholmann’s (the original poster) request for suggestions on how to improve the design. What doesn’t work? What does?

When someone is asking for my money for a charitable purpose, I want to know first if it is a worthwhile cause, and second if I trust the organization to spend the money wisely. This brochure does convey that this is a labor of love for some passionate individual or small group, but what the design does not do is give me a sense that this group will be around long — who knows what will happen with their passion next year? Sure, wheelchairs for kids seems like a good idea, but wouldn’t my money be better spent giving to a large organization like Doctors Without Borders that might prevent the reasons kids end up in wheelchairs in the first place? The brochure doesn’t seem to explain why these wheelchairs are so important in the face of all the other problems that their recipients face.

For example, the brochure reads, “For most, life lacks no hope. No education. No schooling. No chance of getting a job.” And a wheelchair is going to help how, exactly? Now, if they had given a case example of a few children and how their lives had been improved by having a wheelchair, of how they could now attend school where they couldn’t before, or something like that, that would be a lot more convincing.

It seems that what this brochure needs is more than just a facelift. Any responsible designer would first suggest a rewrite of copy, right? How design and copywriting overlap would be a great discussion for the future, I think.

Again, very valid points!

Agreed. Copy is so important. That double-negative in there (life lacks NO hope . . . !?) says that these poor kids in wheelchairs have all the hope, education, schooling and chance of getting a job that they need!

I agree with the good-design-is-necessary comment, for sure. A copy rewrite is also needed here.

I work for a nonprofit that recently began working with a marketing agency. We’ve gone through an entire “rebranding” process that only seems to be helping our organization obtain support and assistance.

Thank you for this post! I’m thrilled that so many others seem to share my thoughts exactly! I’m currently working at my church as the graphic designer/communications manager.

Though I haven’t read all of the comments, I will say that while some not-for-profits may truly need a pro-bono project done, I still think that they should pay for design services at a reduced rate. They need to understand the VALUE of design that effectively communicates their mission.

I agree with all that has been said here. Especially @Amber (It would help, however, if they were to print “design and printing generously donated by _________” on the promo piece itself.)

And I would add to that a line that says: How can you help? To maybe encourage others who have talents, but not much in the way of $$ to contribute their labor/skill set for say Facebook page setup and maintenance, website design and other areas.

Great ideas. And John, I would love to see you re-design this brochure. I love your style and look and that you add such simplicity to design.

Thank you, members, for your insightful postings.

As a member of a family that is often asked to contribute to charities, I will echo what many are saying here: a non-profit needs a polished presentation with a clear message of who they are and what they do.

What impresses us most, however, is if they can convince a talented designer to donate their services for a logo and/or brochure (a small “special thanks” in the credit text is important). If a busy, talented designer feels their cause is important enough to support, then the organization is worth a further look.

A “too-designed” design is usually a tip-off that all your donation is going to buy is a place of honor in the appeals database.

Thank you, John, for making me a better observer.

I don’t think I’d approach this brochure differently than any other. I would still look at what it’s trying to say, and to whom. Then I would create something beautiful. End of story.

The brochure in question is over-designed — too many effects, too many lines, competing fonts, etc., etc., — not enough simple communication.

I’d approach this like John says: “Design like a lazy person.” Big photos of the people in need, simple headings, and a call to action. I think the result would be more powerful and the message communicated better.

By the way, if you’re dealing with ho-hum, unprofessional photography, a high-contrast grayscale or duotone can rescue the worst of images.

The problem for a non-profit organisation is that a well-designed piece usually takes a good designer who is worth more spend, so charities should get a little more active in asking design-community blogs for help. Someone, somewhere, will have some time to give, I’m sure.

First of all, I’m agreement with all that’s been said and written.

Second, I have a slightly different take.

To me, the goal of design is singular:

Get people to read, understand, and respond.

Anything and everything that gets in the way of that is bad design.

My brain looked at that mess and told me: “I can’t read that.” And so I didn’t even try. I have too many things to do in my life to spend time trying to read something that my brain tells me is too difficult. And all our brains are exactly the same! As designers, we have to get the reader’s brain to say, “Oh, I can read that!” And then it will get read.

If that’s so, and to me it is, then I start with understanding what makes for good and easy reading so the brain will encourage my work to be read by the person who interacts with it. To me, that means:

a. Generally, serif body type. It’s the type we learned to read. Thus, it is our default. Anything that’s different HAS TO BE TRANSLATED BY THE BRAIN EACH AND EVERY TIME. (Just like all those caps have to be translated to lower case. You many not realize your brain does that, but it does. And that translation takes time and causes the brain to say, “Oh, this is too hard.”)

b. Standard leading and word spacing (I don’t want to hear about “I was trying to air it out, give it a little breathing room”). Once again, our brain has a default it expects to see. Don’t fight that expectation if you want your copy to be easily read — which is my goal in design.

c. A headline that speaks specifically to the intent of piece. (BTW, that’s one of the first things I do — ask them what they want the reader to do. And please, don’t ask them to do much. One thing is probably enough.) Headlines that are specifically vague (Now you can help the children of the world!) do not work anywhere as well as headlines that are specific (Will you help us buy wheelchairs for children?).

d. Then look at the hierarchy of thought and action. Where does the copy go? What picture best tells the story quickly and powerfully, what typeface works best with all these elements? etc.

e. If the copy is poor, rewrite or have it rewritten. Simple words, short sentences. No sense in getting them willing to read only to have them burn out on incomprehensible phrases, fluff, and filler.

f. Then look at the techniques of design: spacing, white space, elements, flow, etc. Tweak them and evaluate your changes. I keep trying to simplify as I go. What can I get rid of to make my work stronger, more effective, and more likely to be read?

I have taught several non-profit folks these things, and virtually all have been able to implement them in their own work. (Teach them to fish . . . )

The more I read Before & After, the more I design, the more I evaluate the design I come across in the world, the quicker and easier it is for me as a designer to recognize the problems within an existing piece and fix them so that it works. That’s really an amazing feeling. Especially when someone says to you, “How did you know to do that?”

When that happens, I thank my teachers.

Thanks, John.

P.S.: I am also amazed when I seem to forget everything I know. That’s when I go through my back issues and my Master Collection CD!

[Translated from Portuguese by Google Translate. Original text is at the bottom.

Despite a reasonable understanding of English, I do not dare to write in that language.

I have done many jobs for nonprofit organizations. In 2009, I even spent 15 days giving a workshop in Angola Production Graphics and collectively building an agenda of employees working in the area of communication of such an institution.

I would like to draw attention to some points raised:

1) Good design does not mean a nice design but, first, adequate for what you want to communicate and the audience for which it was intended.

2) Therefore, a graphic piece is not even cheaper or more expensive because it has a better design. Because the type of paper used and graphics (such as folding, special knife, UV varnish, among others) will be thought of in view of what is defined in the briefing — what the customer (nonprofit organization) wants to communicate and the public target (by the way they think, see) with whom you want to connect.

3) Most important in the design of a graphic piece is the organization of information (whether written or visual only) that it considers essential to convey.

The workshop that I taught in Angola was a fantastic experience for me. The agenda was collectively built, from the editorial proposal for a reference to the construction of a visual and graphic design. What we really tried to move onto in the professional organization has been my experience over 20 years in the area:

a) rationalizing the distribution of the content proposed in view of the industrial process of printing (close to 192 pages, printing 2 × 2);

b) introduction of desktop publishing programs (which they already knew in part) from a vision of the work of the designer/producer;

c) concern about the technical details such as size and resolution of the images (I got to generate a PDF test and went to a printer from Luanda to make sure that there would be no problem in CTP or photolithography).

Unfortunately, when dealing with this organization, I have often encountered a situation that is not good: The contact person does not have any knowledge in terms of communication but also does not accept talk about it. Often, it is possible to build a simple briefing pamphlet (as an example to give the starting point in this discussion): The organization wants to put all the information she imagined (even if, in fact, unnecessary) or talking to all sorts of people, and insists that the material is printed on this or that paper (here in Brazil, on couch), among other things.

—————

[Original text]

Apesar de compreender de maneira razoável o inglês, não me arrisco a escrever nessa língua.

Já realizei muitos trabalhos para organizações sem fins lucrativos. Em 2009, inclusive, passei 15 dias em Angola ministrando uma Oficina de Produção Gráfica e construindo coletivamente uma Agenda com funcionários que trabalhavam na área de comunicação de uma instituição desse tipo.

Gostaria de chamar a atenção de alguns pontos levantados:

1) Um bom design não quer dizer um design bonito mas, em primeiro lugar, adequado para o que se deseja comunicar e para o público ao qual ele se destina.

2) Por isso, uma peça gráfica não fica nem mais barata nem mais cara por possuir um design melhor. Porque o tipo de papel utilizado e de recursos gráficos (como dobra, faca especial, verniz UV entre outros tantos) vão ser pensados em vista do que for definido no briefing: o que o cliente (organização sem fins lucrativos) quer comunicar e o público-alvo (com sua forma de pensar, de enxergar) com o qual se quer entrar em contato.

3) O mais importante no design de uma peça gráfica é a organização da informação (seja ela escrita ou só visual) que se julga essencial transmitir.

A Oficina que ministrei em Angola foi uma experiência fantástica para mim. A Agenda construída coletivamente, desde a proposta editorial até a busca de referências visuais e construção de um projeto gráfico. O que realmente tentei passar para os profissionais da organização foi minha experiência de mais de 20 anos na área:

a) racionalização da distribuição do conteúdo proposto tendo em vista o processo industrial de impressão (fechamos em 192 páginas, impressão 2×2);

b) apresentação dos programas de editoração (que eles já conheciam em parte) a partir de uma visão do trabalho do designer/produtor gráfico;

c) preocupação com os detalhes técnicos, como o tamanho e resolução das imagens (cheguei a gerar um PDF de teste e fomos até uma gráfica de Luanda para ter certeza que não haveria problema na hora da saída do material em CTP ou fotolito).

Infelizmente, ao lidar com esse tipo de organização, tenho me deparado muitas vezes com uma situação que não é boa: a pessoa de contato na instituição não tem conhecimento algum em termos de comunicação mas também não aceita conversar a respeito. Muitas vezes, não é possível construir o briefing de um simples panfleto (como o colocado de exemplo para dar o ponto de partida nesta discussão): a organização quer colocar todas as informações que ela imaginou (mesmo que, na realidade, desnecessárias); quer falar com todo tipo de gente; faz questão que o material seja impresso nesse ou naquele papel (aqui no Brasil, em couchê), entre outras coisas.

Good topic and discussion!

As graphic designers, we all strive for a piece that is attractive, effective and represents the client. Unfortunately, this can be difficult with non-profits because they often don’t have professional copywriters, photographers, etc. and we need to create a fabulous entrée with inadequate ingredients.

But it’s a challenge worth taking on. Most of my work is for non-profit arts organizations, and I really am fulfilled by helping them create quality marketing pieces. Plus, with digital printing and less-expensive coated sheets, slick is no longer indicative of expense. I’ve found that most donors are not turned off by a quality piece; rather, they appreciate the organization’s attention to details.

My belief in “perceived quality” was reinforced by one particular example: Our community symphony was searching for a new music director, and the season brochure attracted a talented prospect from out of town because he was impressed that the group was presented so professionally.

From the point of view of a person who is not a designer (but wishes she had the talent to be one!), but who does respond to charitable missives, the one thought that immediately goes through my head when I see a poorly executed brochure/flier, etc., is “how much money did they spend on this horrible piece?” Just as we may equate wasteful spending on slick design, we also equate wasteful spending on bad design. Neither gives me a good feeling about donating my hard-earned money.

Secondly, a poorly designed, cheaply produced piece gives the impression that the charity isn’t invested in its own future. To me, that points to a fly-by-night operation that is merely trying to raise funds for its principals and then disappear into the night. Unfortunately, the Wheelchairs for Kids brochure falls into that category for me. Were I to receive this brochure, I would think “scam” and toss it into the nearest recycle bin.

Good design and bad design can be had for the same price (yes, even free), so why not side with good design and make the most of the opportunity it affords?

From my experience with a non-profit, they are never offended if you over-redesign something. I recently redesigned a website for a local cat shelter, and they loved it. The original was loud and unorganized, and the sad part was that a local, professional web-design firm had made it for them! In no time I had created a much-more-professional-looking website that now gets more hits. So it’s worth it to help out these charities, because the better-looking the design, the more apt people are to look at it. So go for it and help them out; they’ll really appreciate it. Here are the websites: New Old

Aaah! The old site made my eyes bleed. It might’ve been considered a good site . . . in 1997. Seems as if they haven’t felt the need to keep up on their web tools.

Good job, Adrianne!

I won’t give to any charity that I know spends a lot of money in advertising or administration. Of course, what is “a lot of money” is debatable. One sign I look for are the credits in the print material. I’m in the print business, and when we donate print costs to charities they let us put our credit in the usual, inconspicuous bottom corner.

I think everyone wants to give something back to society. Why not give some of their time and talent to charities who need it most? Seeing the credit in a brochure assures me that at least the charity is spending some advertising money wisely, and that catches my attention and appreciation.

Great post and comments. There’s a lot to be learned here. I am grateful to you, John McWade, as well as to all who responded. I pick up whatever I can.

I have been involved in a lot of charity work over the years and am often called to “design” something. I am not a professional designer, but I work in a creative field, plus I have worked for and attended classes at an accredited design school. By default, that often makes me the “expert” in the room.

I find that design can be an afterthought — “We worked so hard to pull it all together, so let’s slap together a flier to invite/inform people. What’s the big deal?” It is important, though. When I try to point out (or show) how great good design can be, I get the distinct feeling that I am not quite believed.

I agree with John . . . when it comes to not-for-profit and causes, you kind of have to throw the marketing book out the window in many respects.

In these cases, it’s absolutely crucial to humanize the project, the cause, the organization, and the best way to do that is to focus on founder stories — what drives the founders to forsake all to do all this for usually no remuneration to speak of? Many not-for-profit founders are uncomfortable about stepping out into the limelight, but it’s what can help propel their organizations. Women for Women International’s Zainab Salbi has achieved almost rock-star status, but with her fame she raises about $11M annually via e-mail alone!

Founder/Organization folklore . . . company stories that convey the spirit and energy and motives behind all that happens.

And, of course, focusing on the recipients on a personal level with stories and individual photos (think kiva.org) that communicate the life-changing effect donations and involvement can bring to another human being.

So, I think design has to take these personal elements into consideration. Tougher to do in a small brochure than on a more-expansive canvas like a Web site.

Agree with John. We need to work with the particular nonprofit organization and come up with a perfect design for them. Good design is about what is perfect for the particular need. If the nonprofit team thinks a particular design is too “flashy” for them, then it’s not a good/correct design for the cause.

The example Mark Scholmann shared is not a good design, since none of the information catches my eye, and I don’t feel like picking it up from any brochure stand. Too much info is bombarding for people, and many a time they just don’t pick up the brochure for the fear of deciphering the actual message from the whole lot of information. Information needs to come at the second stage, when a person has decided to volunteer as an unpaid employee.

If a marketing piece didn’t arrest the attention of the people, then there is no problem with people thinking that the piece was a “kitchen-table design,” and that it is so because “the charity is handling the contribution truthfully and well.” If, on the other hand, a marketing piece, after getting noticed, conjures up such questions in the viewer’s mind, then it’s definitely not produced keeping in mind the need of the marketing piece or the job the piece needs to perform.

As someone who works for a non-profit and plays a very large role in helping set the parameters for our materials (website, brochures, etc.), I appreciate the conversation. Lots of good stuff!

Several years ago, we looked at what we were doing and did a revamp on most things, though we were working with volunteer help, and being overseas it was difficult for me to co-ordinate things. One thing that was amazing for us was re-doing our website. We worked with a friend who wasn’t a pro, by any means, but had a good eye for things. We took our time and hacked through things. I can’t tell you what that revamp did for our org. It was probably the single most effective thing in helping push us to the next level. It was organized, reflected who we were, etc., and gave people the impression we were bigger than we were.

We just recently did another revamp using that same friend, who had picked up some new skills in the last couple of years, and we couldn’t be happier with what came out of it. Daily, we’re receiving donations through online giving from people who have had no known ties to our org in the past. To me, that says that they’re finding the info they want, they can see the value of what we’re doing, and they can see how to get involved. The design is the vehicle to do that, and apparently it’s doing it well.

We’re now in the process of doing a revamp on all of our printed materials, and it’s my goal to beautifully tie everything together in a cohesive package so the business cards and brochures and donor cards all have some consistency. I think this speaks to the quality issue that has been talked about. It says we’re paying attention and we want to represent ourselves well. We’re serious about what we do, and donors can have confidence in what we do. That confidence and seriousness is one of the most important things we can put out there. It feels good to tell people what we’ve accomplished and to know that our image reflects that. We’ve seen a good response in the past, and I’m looking forward to seeing how this attention will help move us forward to the next level.

A little late to the party here, and just enjoyed reading all of these very astute comments, but as someone who cut her teeth designing for a printing company in the cut-and-paste (and film-to-metal plates) age, and then taking the freelance route once the Mac made that so possible and affordable for all of us, I do have some opinions on some of the remarks made about keeping the printing affordable, in addition to a couple of others:

AMBER: Bravo, especially on the extra-postage sizes. My clients all love square envelopes. Until I caution them to budget the postage before we go to press. It’s a lot of money if you’re mailing thousands of event invitations.

STEVE, who advised against handing design over to a kid filling a portfolio, rather than an experienced “agency.” Sorry, but I cannot tell you how many non-profit clients I’ve acquired because an agency refused to change a pro bono design, and the resulting piece was more about the agency’s portfolio than the non-profit’s message. Worse is when they insist on “brokering the printing,” and the non-profit is not even allowed to get competitive bids on their own — or even know who did the printing. It happens all too often in my neck of the woods. It goes both ways.

Non-profit readers here, please do not allow designers to bully you into “brokering the printing.” You should always know who is printing the piece, and how much the printing costs. Let the designer be upfront and tell you if there’s a percentage mark-up for them to handle the printing. Be very wary of designers who have exclusive relationships with printers. This is doing a disservice to non-profits. The designer deserves to be compensated for the time involved with acquiring competitive bids and managing the printing, especially on large, complicated projects, but it should not be a hidden cost.

GEORGE, who advised advised against expensive print embellishments (true dat), but included “aqueous coatings” in his list. If your piece has a long shelf life and heavy ink coverage, such as an annual report or capital campaign case statement, you would be penny-wise and pound-foolish if you skipped the aqueous coating. Unless it’s a spot or special varnish, most readers will never even detect a coating or varnish.

BARB, who works with several non-profits and bemoaned the fact that they could not get a 22 x 8.5 piece printed. I assume you mean 22 x 8.5 FLAT, folding to 11 x 8.5. This is not an odd size. It conforms to a standard 22 x 17 flat size. Please don’t think the designer did you wrong. Rather, you were likely dealing with printers with very small presses, very small print shops, or shops doing only digital printing or color copying on 12 x 18 or 13 x 19 sheets. Any offset printing company should have been able to produce this piece. It’s actually a good format, provided it goes to a true offset printer, as it capitalizes on the size of standard press sheets with no waste factor involved, while providing an interesting panoramic format, one that still fits a standard 9×12 envelope. Caveat: the printer must be advised of the location of the fold, as the grain direction of the paper could affect how well it folds.

JUNE, who advises, “use two-color for print.” Sadly, these days going to an online, full-color printer is almost always more cost-effective than going with a local printer who still runs two-color presses, especially for non-profits, which often have much lower press runs and print smaller pieces, which are not cost-effective to print locally. My advice is to get estimates from local and online printers. The local printers will still be cost-effective for multiple-page projects with higher press runs, whether it’s two-color or full-color, and especially for multiple component projects that might require stuffing, sealing, mail processing. But the online printers are vastly more competitive for postcards and brochures, especially at smaller quantities.

PAUL, who advises two-color (even if it’s a duotoned image converted to CMYK) or high-contrast grayscale to rescue poor-quality photos: BRAVO. You take an inferior image and give it “mood” by applying either treatment, and most non-profit images need to have mood — they are not catalog items. Really good advice, as few non-profits can afford professional photography.

RANDY, who advises using serifs, in general. Traditionally true, but you are missing out on a lot of wonderful new font-family designs that straddle the fence between serif and sans-serif. These are fonts designed specifically for text-heavy use, with legibility in mind, and are complete families with several weights, true small caps, old-style figures, even display versions. So, designed with tradition in mind, but a little more contemporary and often easier to read at smaller sizes than, say, Adobe Garamond, whose small x-height and fine serifs can be too difficult at smaller sizes.

Really enjoyed the discussion and learned a lot. 100% of my work is for non-profits, and I truly, truly love my work.

Johanna, if those hybrid fonts make me want to read the copy, I do use them, if they are appropriate. “Missing out” is not a consideration for me. Likewise, being “contemporary” is less important to me than encouraging reading. True, AG can be hard to read at small sizes, which is why I have many other serif alternatives. The final choice of type should make the piece feel better but, more importantly, make it easiest to read. John once said that all he needed was Century Schoolbook and a few display faces. I took that to heart.

If you learned to read in Europe, this conversation would be reversed — sans serif was the font of choice in their readers.

You may also have noticed a switch in online usage from body copy in sans serif (almost to an exclusion) to serif body copy. This is due to the vastly improved monitors we now have. Personally, I can tell when printed copy has been lifted from the web because they often do not change the font, and my brain tells me “this is too hard.”

Non-profit does not mean “no budget” — the proceeds are simply fed back into the business. If you have individuals who believe in the cause and put forth their best efforts, the budget will be more wisely utilized, resulting in a more-complete and modern product.

I have been working as the designer for a non-profit organization whose mission is to provide continued support for troubled individuals and families who have either completed a mandated program or are in need of getting back on their feet.

While the budget is not large, I have taken on the design effort personally, offering continued hours upon hours. Our organization relies mainly on donated time commitments of our Church. Because of this, we have one mind and goal.

A local printer recently commented that a brochure I created was the best he had ever seen. So, should non-profit be designed with the same level of effort as a high-paying client? Absolutely, if you believe in the cause. And I do.

I love this topic — I’ve often wondered the same thing. But taking it one step further: Does “bad design” in print work the same way it does in TV/radio? You know, those awful, annoying cheesy ads that just stick in your head? You end up remembering the phone number of the company just because of the stupid jingle!